Comic Book History: The Comics Code Authority

POSTED January 6, 2020

In 1954, a book that criticized comic books named Seduction of the Innocent was published. Later that year, the Comics Code Authority was enacted. This shifted the Golden Age into the Silver Age of comic books and with it, destroyed most of the variety in comic book genres.

The Comics Code Authority (CCA) was created by the comic book publishers to prevent backlash from the comic book community. One interesting point about the code is that it was self-regulated and not an official government policy. The CCA was made up of the publishers themselves. The code was created that way so it wouldn’t have as harsh censorship via the government.

The authority then created a set of rules that pulled back characters and other genres of comics for years. Some points were reasonable such as “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible” and “females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.” On the other hand, there were rules like “advertising for the sale of fireworks is prohibited” and “no comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title.”

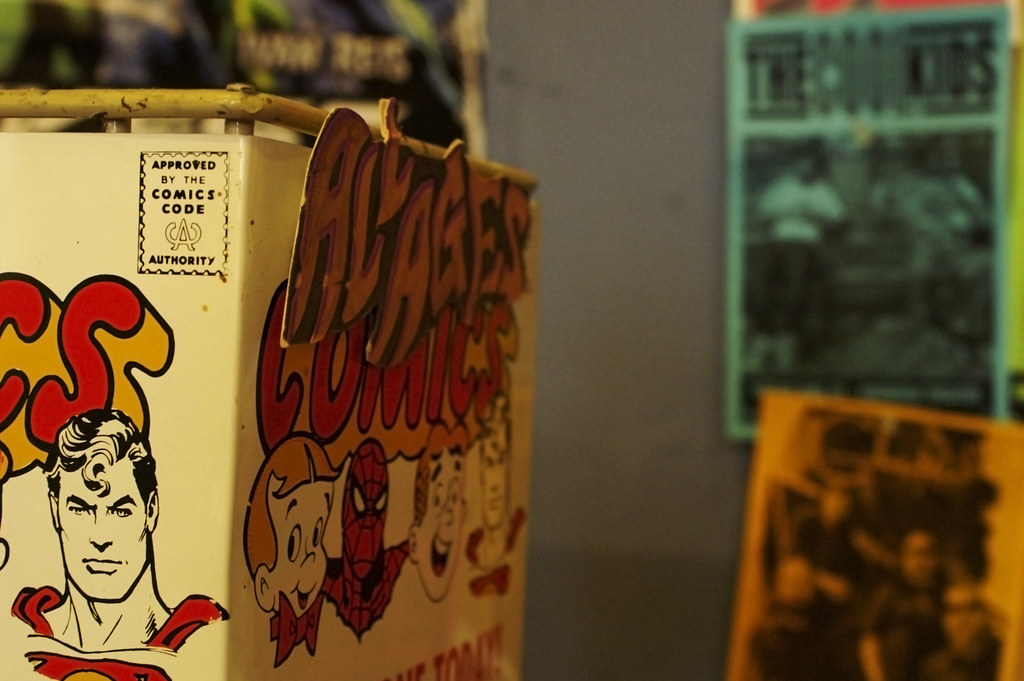

From there, companies either had to shut down or comply to the rules. Despite that the code wasn’t a government standard but a general standard in the comics community, comic book sellers would refuse to hold books that didn’t have the seal of approval. This served as a reinforcement to ensure that the CCA had power to enforce its laws.

William Gaines, the publisher of Entertainment Comics (EC Comics), believed that he was being deliberately targeted by the CCA. His most famous titles, Crime SuspenStories, The Vault of Horror, and Tales from the Crypt, would be taken down via the CCA’s rules. The rules about which words can be in titles and the rule that banned vampires, werewolves and zombies lead to EC Comics’ downfall.

In response to this, William Gaines created the Mad Magazine. EC’s failure at creating comics that could be accepted by the code and a problem with republishing a story led to Gaines deciding to focus on Mad. As a magazine, Mad didn’t have to comply to the same guidelines as comic books which allow free publishing.

Another way to work around the CCA was underground comix. These were unauthorized and self-published comics that were usually comical or political. To create a difference between normal comics, underground writers called them comix. The “X” was to also emphasize that the comics were X-rated. These comix kept to their rating with content and artwork.

Some interesting situations arose as a result of the code such as conflict with Marv Wolfman’s last name. In DC Comics’ House of Secrets #83, the book’s host said that the story was told to him by “a wandering wolfman.” Due to comic book lettering being all capital, there was no distinction from wolfman and Wolfman. Werewolves in comics was a violation so DC Comics had to explicitly state Wolfman was a writer.

One event showing the problems with the code was when the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare asked Stan Lee to write a Spider-Man story about the dangers of drug addiction. Lee agreed and created a storyline showing the dangers of drug use. John L. Goldwater of the CCA refused to print it because of the depiction of narcotics being used even when it’s presented in an unpleasant fashion. Marvel decided to print the story anyway without the code.

DC Comics was also planning a Green Arrow comic that attacked drug use with Green Arrow finding out his partner Speedy was using heroin. The editor, Julius Schwartz, rejected the story as it wouldn’t comply with the CCA. After Marvel’s Spider-Man story published, DC, Marvel, and other publishers rewrote the CCA and then the Green Arrow story was put up.

The new revisions to the code lifted the ban on horror comics (although the ban on using the words “horror” or “terror” in titles still stood) and there were fewer restrictions on crime comics. Rules about how to handle drug use in comics was also created. Although by 1989, a new version of the code was created.

Comic book distribution shifted and allowed for comics not approved by the code to be sold. At this point only Marvel, DC, Archie, and Harvey Comics was still using the CCA; half of the publishers wanted the old code, the rest wanted a new one. It was decided the CCA would use a new code which gave broader guidelines. This didn’t matter as much since specialty comic bookstores opened and didn’t care whether the code was used or not.

In 1994, Harvey Comics went down leaving only three major publishers. Come 2001, Marvel decided to stop using the CCA in favor of their own rating system. It wasn’t until January 2011 that DC announced it was dropping the seal and shortly afterwards Archie Comics followed. Afterwards, Archie Comics said they were not submitting their comics to the CCA since 2009.

DC was the only publisher submitting their comics by the end and no evidence was seen that the CCA was even in use past 2009. This leads to the question of who was reading and approving every issue sent? One woman named Holly Munter Koenig kept the CCA alive until DC’s announcement. The Kellen Company, who oversaw the Code, stopped supervising so their senior vice president, Koenig, read every single comic submitted.

After all publishers stopped using the CCA, it went officially defunct. Companies came up with their own rating systems for personal regulation. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund took over the Comics Code Authority’s symbol which was the final page in the CCA’s history, the guidelines that changed comic book censorship forever.

Mathias • Jan 16, 2020 at 4:03 pm

This was a very interesting read! I never knew that comics had such a fight with self censorship. Very well made a fantastic article! Keep up the good work.